Abuse of children at Marylands School in Christchurch was so rife it was described as a state-supported, church-run brothel for paedophiles. But so far the spotlight has focused on a handful of individual abusers. An inquiry this week tried to find out how deep the rot went.

photo / Royal Commission of Inquiry

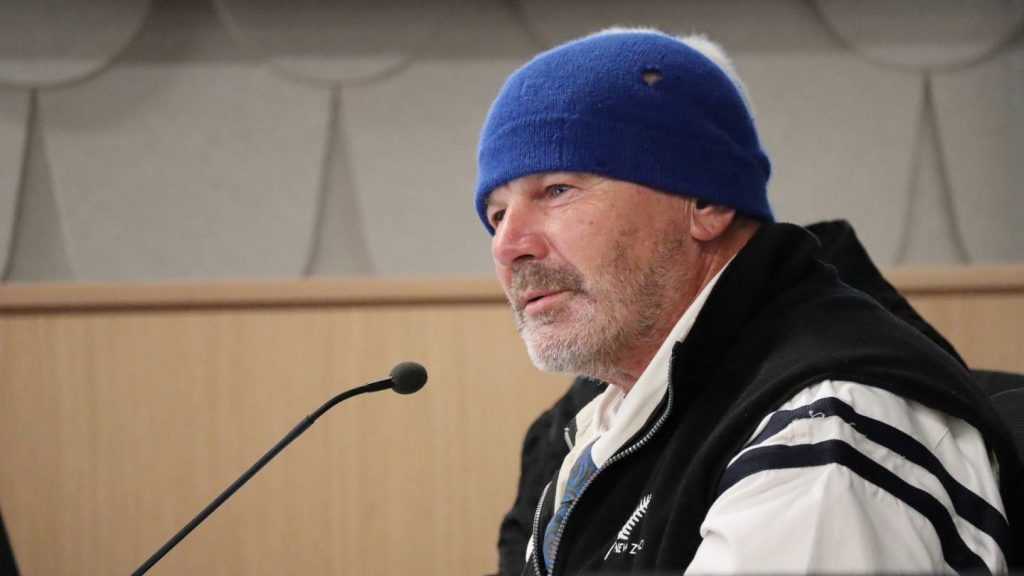

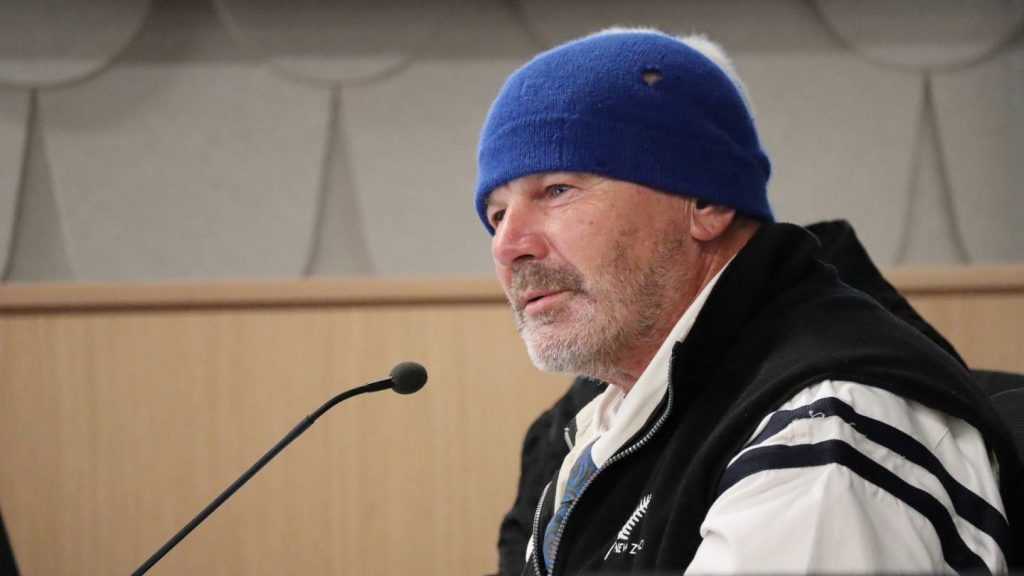

Alan Nixon nearly had to burn a church down to get noticed.

After Nixon racked up 400 convictions including arson, vandalism and burglary, his lawyer eventually asked him why he had targeted church buildings.

Nixon told a story he had already told many times: He had been sexually and physically abused at a Catholic school, Marylands, in the 1970s. Any building with a steeple reminded him of the school in Halswell, Christchurch, which he attended from age 8 to 14.

He had told police the same story 30 years earlier after they caught him running away, but later found in their records that they thought he was a liar and “not a very bright person” (Marylands was for students with learning difficulties). Social welfare and other state institutions also dismissed his story.

After Nixon told his lawyer in 2002, something finally happened. The Hospitaller St John of God religious order, which ran the school between 1955 and 1984, met him. He was paid $1500, and promised long-term support. Yet that promise was never fulfilled.

Nixon was in and out of jail for 30 years after he left the school. He now lives outside Christchurch with another survivor of abuse. He has Parkinson’s disease, which prevents him from working.

“I’m coping, trying my best to enjoy life, although I still struggle with PTSD symptoms,” he told a Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in State Care last week.

“It’s still hard. If I had the accommodation, transport and counselling support that the St John of God Order had promised me, life would be so much better.”

The abuse at Marylands has been publicly known for 20 years. It is particularly infamous because many of the victims were disabled. They were removed from broken homes and broken again by abuse, many of them doomed for life.

Former Brothers Bernard McGrath and Roger Moloney were jailed for sexual offending in the early 2000s and Raymond Garchow and William Lebler were charged but never went to trial because of their ill health.

The St John of God is a tiny religious order in this country, barely a footnote in the history of the Christchurch diocese. But it has had an outsized role in abuse within New Zealand’s Catholic Church – 14 per cent of all recorded abuse since 1950 occurred at the hands of its members.

Hearings in the past 10 days in Christchurch aimed to go a step further than the criminal prosecutions and investigate the role of the order, the Church, and the state in the abuse at the school. Some victims were speaking for the first time, up to 50 years after they were abused.

The commission heard from Dr Michelle Mulvihill, a former nun in Australia who became a psychologist and helped St John of God respond to sexual abuse claims. Her extraordinary testimony, based on years of inside knowledge of the order, showed that Nixon’s experience was not isolated – it was typical.

She visited New Zealand 13 times with Brother Peter Burke, the regional leader of the order, to track down 70 victims who had reported abuse at Marylands School.

They found the victims in prisons – in Hawke’s Bay, Invercargill, Paparoa and Rolleston. Others were homeless. One was sniffing glue and during their meeting vomited all over the table. Up to 95 per cent had mental health problems.

They met a man in Invercargill in a shared flat whose total possessions were a single bed with threadbare sheets, a side table, lamp and a chair. The house was freezing, but he proudly displayed a heater he had borrowed for the visit.

Burke, the most senior member of the order in Australasia at the time, and Mulvihill sat on the floor and heard the former student’s story of abuse and its toll on the rest of his life, his lost relationships and the removal of his children.

“This was typical of the kind of victim that we met in New Zealand,” Mulvihill said in her written submission.

Burke gave the man $50, arranged another payment, and promised he would be looked after, Mulvihill claimed.

“He was never followed up or contacted again.”

This happened again and again. Mulvihill indicated that Burke was sincere in his wishes to support the men, but was steamrolled by the order’s leadership.

“After many years of trying to assist the order in understanding the depth of the problem of sexual abuse by perpetrators inside their own order, it became clear they were unwilling or unable to take any steps to remedy the situation,” she said.

“There is still a culture of hiding information, of not trusting the police or victims or their families.”

Brother Timothy Graham, the head of St John of God in Oceania, rejected his former colleague’s claim that the order was in “organisational denial”.

”The brothers feel the pain and anger of the victims very deeply,” he told the commission.

St John of God is a lay congregation, meaning its members are not ordained. But victim advocate Ken Clearwater, who has represented Marylands survivors for 20 years, said the broader Catholic Church could not wash its hands of the abuse. It recommended the order establish itself in Christchurch and was responsible for overseeing its activities, he said.

Catholic Archbishop Paul Martin downplayed the accountability of the Church in a hearing this week, saying bishops could not be closely involved in everything going on in their diocese.

Nixon felt the state had also got off the hook for the abuse at Marylands. Social welfare placed him there, ignored his complaints and failed to monitor him. He was eventually paid $40,000 by the Crown (“chump change”) in a settlement he begrudgingly agreed to because he had been fighting the claim for 12 years.

“I want those in authority to own up to their wrongdoing — particularly the St John of God Order but also the Ministry of Social Development,” he said.

“They need to be more transparent and take care of the people who were hurt, rather than just protecting their own people. They need to take responsibility for what their people did — they can’t just brush it under the carpet any more.”

By Isaac Davison

19/02/2022