At Marylands School, sexual and physical abuse by Catholic brothers was brutal, prevalent and normalised. Survivors were so traumatised that, after they left, they found it difficult to understand the boundaries between right and wrong.

Photo:

This article is part of The Quarter Million, exploring the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in State Care. Read the introduction here and the rest of the series here.

Content warning: This feature describes physical, sexual and emotional violence, child abuse and neglect. If this is difficult for you and you would like some help, these services offer support and information: Auckland specialist service Help, 0800 623 1700; specialist men’s service Male Survivors Aotearoa, 0800 044 334; and Snap (Survivors network of those abused by priests). Please take care.

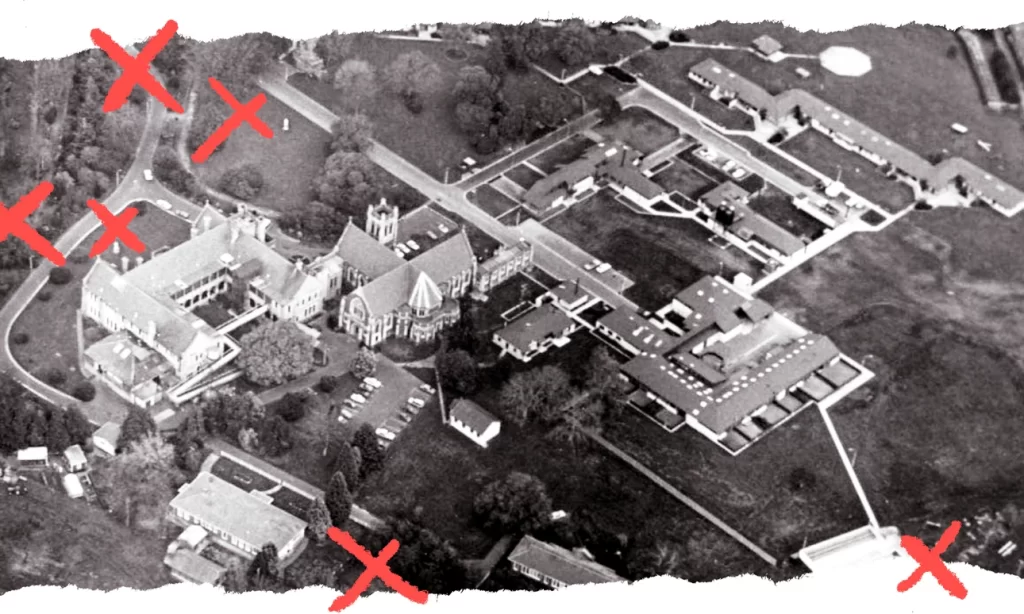

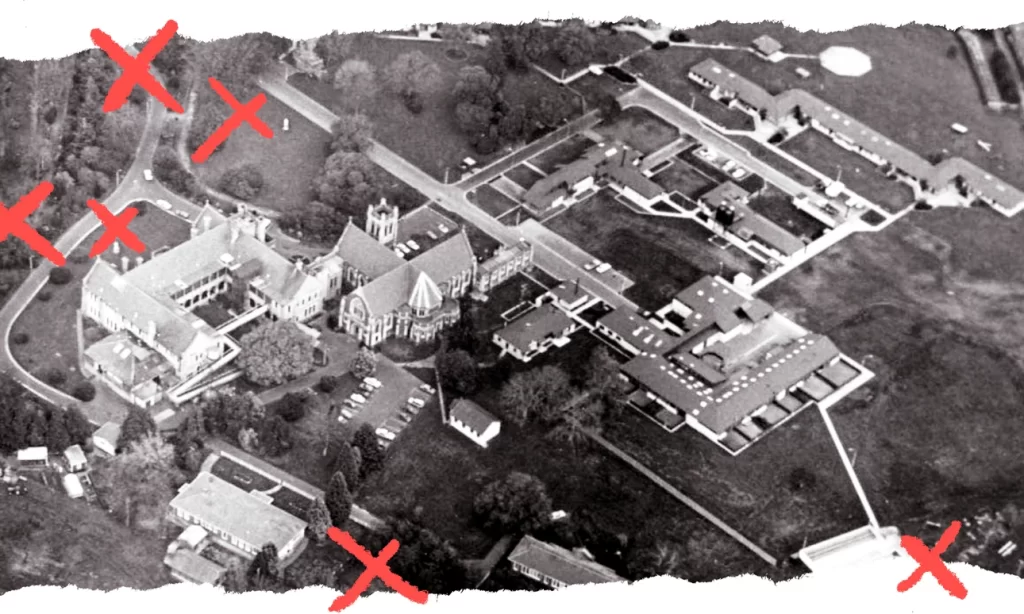

At the frayed edge of Christchurch, the city dissolving into large fields and fast roads, there’s a cluster of buildings that look towards the spiny line of the Port Hills. This is the Halswell Residential College. Today, it’s a school that has boarding and day options for kids with a range of difficulties, including emotional management and intellectual disability. Run by the Ministry of Education, its website is filled with glowing reviews and reports from students and parents about their time at the school.

But nearly 40 years ago, this was Marylands School, run by the St John of God Brothers of God, a Catholic order supposedly dedicated to education and healthcare. Marylands was described to parents and the community as a place to educate children with intellectual disabilities and other difficulties. Initially based nearby in Middleton before moving to the Halswell site in the 1960s, the school was open for 29 years, between 1955 and 1984.

It was an “evil place,” says Ken Clearwater, a survivor advocate who has worked with the Male Survivors of Sexual Abuse Trust (MSSAT). A recent report titled Stolen Lives, Marked Souls, following a case study hearing as part of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, found hundreds of children were sexually, physically and psychologically abused at Marylands. Many survivors feel that a redress process conducted in the early 2000s was inadequate. They want this bitter history to be remembered beyond those who survived it, because they don’t want abuse like this to ever happen again.

‘Marylands was all I knew’

Eddie Marriot remembers the school crest of Marylands, a kind of seal that was everywhere in the school, including on reports sent to parents. In the centre was an icon of a boy curled up nearly in the fetal position. Marriott, who lived at Marylands from age five to 15, the longest resident, often imagined that the small boy was him. One of the youngest children to ever come to Marylands, he slept on his small bunk near a window, spine curved, sometimes shuddering with nightmares that still plague him. Marriott was often told he had been at the school so long he should know the rules of Marylands; he felt as if he was identified with the place, unable to imagine who he was beyond its walls.

Now in his 50s, surviving on a benefit and living in Christchurch, Marriott remembers being taken to Marylands as a small child. Told he was a “slow learner” from a young age, his parents’ house in Morrinsville was a violent place: one of his earliest memories is his dad holding his face down in a bathtub of water. In and out of care from his toddler years, he remembers the thrumming motor in the ferry on his first journey to Marylands; the landscape flicking by out the door of his father’s white Vauxhall Viva.

When he arrived at the school, it struck him as an imposing place, with big gothic buildings and courtyards of stone. The floors were smooth and shiny; they had just been polished. In brand new shoes, Marriott slid across the floor. “Dad thought I was misbehaving, and said if I didn’t stay still he would give me a beating,” he says, voice cracking over the phone from Christchurch.

Marriott remembers sitting and waiting on a stiff mattress supported by uncomfortable bedsprings, watching as his parents talked to the “little old lady” in charge of the junior students at Marylands. He also watched them talk to Brother Moloney, then the head of the school, in his loose robes. His parents told him they were going on a holiday and would come back to pick him up. He next saw them at the school holidays.

While he got to know the other boys at the school, he didn’t have the language to explain the home background he’d come from. “It was strongly drilled into us [by my parents] that what happened at home stayed at home,” Marriott tells me ruefully. Meanwhile, the school, with its endemic abuse, had similar messages. “We were told they [the brothers] were our parents, our mother and father, and what happened at school stayed at school, too. I didn’t know how to talk about it.”

For the next decade, the place Marriott felt safest was in the plane flying home: not at school, not at home, but in an in-between space, where he was not expected to keep anyone’s secrets. “That was the only time I could be a kid without fear,” he told the Commission.

Meanwhile, Marylands became Marriott’s normal. He would wake up in the morning, strip his bed and make it with perfect hospital corners, hoping it passed the inspection. If it didn’t, he wouldn’t get breakfast. There was an assembly officiated by the brothers most mornings, then school, unless you’d been assigned to work at the laundry or the hospital. After school, sometimes boys would talk to each other or play ball. There were rare school trips, including to a bach the brothers owned, and everyone was taken to church on Sundays.

The support and goodwill from the rest of the community seemed to endorse the school, and Marriott remembers a women’s auxiliary group organising a fête as a fundraiser. “I was told the brothers were doing good, that they were helping me to learn,” he tells me. “They were glorifying themselves, putting on a big show for the community,” But at the time, his misery seemed at odds with the face the school showed to the world. “I think that’s how they got away with it. I didn’t know any better. I didn’t know any better.”

According to Clearwater, “the mana of the brothers was held in such high esteem. That was what allowed it to happen.” He’s on holiday in Australia, but is still happy to speak to me: he’s furious about how badly the children at Marylands were treated, that the attempts at apology have been so inadequate. His many years of advocacy for these men, as well as facing his own history of sexual violence, has made him good at describing the dynamics that perpetuate abuse.

Extreme sexual and physical abuse

The young boys, including Marriott, were under the care of a stern woman called Mrs Welch. The only activity at night was watching Coronation Street with her in total silence. “We had to shut up, and she was harsh on that,” Marriott says. Brother Ambrose would watch, too. He told Marriott that he wriggled too much, and had to sit on his knee. “He said I was jigging around too much and he would keep a hold of me and play horsey and rub himself against me while bouncing me on his knee.”

It was only later that he was able to connect the abuse from Ambrose to another assault: at the age of six, in the lower toilet block at the school, two older students grabbed him, pulled his trousers down, then placed their penises between his buttocks. If he told anyone, they threatened to go to “Lanky Legs”; a name referring to serial abuser, St John of God Brother and teacher Bernard McGrath.

Marriott was also abused by Raymond Garchow, another brother at the school. Garchow started coming to Marriott’s bed at night. Garchow guided Marriott’s hand up his robe, placed it on his penis, and instructed the boy to “do what I do to you”. He came back again the next night to do the same thing; he started kissing Marriott, who still remembers the heavy smell of cigarettes and alcohol on Garchow’s breath. The abuse happened multiple times a week; sometimes in the dormitory, sometime’s in Garchow’s room. Often, Garchow would say that he had forgiven Marriott for being bad, but that the boy just had to do what Garchow wanted.

Marriot’s story echoes the words of many other Marylands survivors, who have testified to the police through multiple investigations, kept each other company at support groups, and spoken to the Royal Commission. Different brothers targeted different boys. Victims of Bernard McGrath, who was eventually convicted of hundreds of cases of child sexual assault in New Zealand and Australia, described to the Commission how he would gather a group of boys and make them strip naked in a circle, then walk around the circle forcing his penis into their mouths.

Many survivors have testified that McGrath anally raped them, too. He hasn’t been convicted of this crime in New Zealand, although he was in Australia. “I think people still couldn’t believe that a priest would do that,” Clearwater says.

There were also sinister threats involving dead people. McGrath showed children dead bodies in the church; one survivor, Donald Ku, described how McGrath once forced him to get into a coffin with the body of a dead nun. Many of the students at Marylands were Māori, but there was no cultural respect or adherence to the principles of Te Tiriti. Instead, some of the brothers referred to Māori students with the n-word.

Mostly, the abuse happened in semi-private spaces. At one point, Garchow had forced Marriott to perform oral sex. When a member of the night staff walked past, Garchow quickly retreated. Once a boy had been abused by one of the brothers he often became a target for the other brothers.

To Marriott and other survivors, the prolific abuse and secrecy created a deeply-warped environment, and the boundaries of acceptable behaviour were completely unclear. Marriott recounts how after his time at the school, sharing a room with a friend, they had a fight. “I thought I had to apologise [by putting my hands up his pants],” he says. “He called me a pervert and smashed my head in.”

At Marylands, physical violence and sexual abuse between the students was also common. McGrath and Moloney, in particular, encouraged boys to perform sexual acts on each other, behaviour that was replicated through the school, in the presence of brothers and beyond.

“Fear ruled that school,” Marriott says. “Bullying, sexual abuse, staff abuse. If you questioned the staff you got the shit belted out of you.”

Marriott participated in this culture, too; understanding it was the expected way to behave in Marylands. He still carries guilt and shame from what he did to other boys, and when he gave evidence to the Royal Commission, he addressed it directly. Looking straight at the camera where other survivors were watching the livestream, he said, “If they’re watching this, I’m so sorry for what I started – once you began, people knew what you were able to do.” Commission chair Coral Shaw acknowledged his apology. “Yeah, it’s a shame I didn’t get an apology from the Church or anyone else,” Marriott replied.

That this abuse was perpetuated by Catholic brothers – held in esteem by the community, representative of the good work of God – adds a spiritual dimension to the trauma, Clearwater says. “A lot of those kids were told, ‘You’re stupid, you’re worthless, your parents hate you, God hates you, we’re doing you a favour by taking you in’. You hear all of that and then this is how they treat you? You’re carrying all of this, these traumatic experiences … and you’re being told you should be grateful you’re in there.”

One survivor was charged with arson for setting fire to a Catholic church after he’d left the school, and many express anger and violence towards Catholicism as a religion. “It blew my religion out the door; I’ve given up,” Marriott says. “Religion has been crushed out of me, but that fear is still there. I was told that if I didn’t pray, I wouldn’t go to heaven, and I still have that fear of what religion can do.”

A lack of education

Clearwater points out that while the rampant sexual abuse in the school was an abuse of trust and power at every level, Marylands also failed in its stated purpose: to educate. Many of the children who attended had intellectual disabilities and needed specialised care, which they didn’t receive. Many other students were intellectually capable, albeit with behavioural issues and often from backgrounds that did not prioritise education. The school promised caregivers and the government that all children in its care would get appropriate education, but they didn’t.

“I only learned to read and write after I went to jail,” one survivor, Mr HZ, recounted to the Commission. Classes were repetitive; when the government took the school over in 1984, they found that many of the teachers did not have the training or skills to be educating others at all. Instead of going to school, boys were sometimes sent to work in the kitchen, laundry or hospital.

“The education was sort of juniorised, we didn’t learn much,” Marriott says. “I think I’d only gotten to the five times table by the time I left school [at 15]. I still struggle with reading, like when people put in all those commas when they write, I don’t know what that’s for.” When Marriott writes now, he writes slowly, in big letters: as a child at Marylands, he was teased for his writing, and it troubles him still.

There was little assessment at Marylands and students were often given age-inappropriate material. “The last year I was there, when the government had taken over, they brought teachers in, and they were surprised how much we didn’t know,” Marriott says. “I was asked, ‘Don’t you know this?’ ‘Don’t you know that?’ and I was scared I’d get the strap if I said no.” Halfway through 1984, Marriott’s parents pulled him out of school after he turned 15 and told him to find a job. He hasn’t received any formal education since.

The lack of education has had a lifelong impact. Marriott struggles to read long chunks of text to this day. It’s impacted his ability to work, exacerbated by getting lymphoma in the early 2000s.

“They weren’t taught life skills, they weren’t taught how to read and write,” Clearwater says. Limited education compounded with mental health issues and intense trauma, he adds, making it much harder for the survivors he has worked with to live good lives.

How the church and the state responded

The tragedy of Marylands is that, if authorities and the Church had listened to complaints raised earlier, it’s possible that some of the abuse could have been avoided. In 1977, then leader of the St John of God Order, Brother O’Donnell, received two anonymous letters alleging abuse by McGrath and Moloney. Soon after, O’Donnell told McGrath he was getting transferred to Australia, where he would go on to perpetrate hundreds of instances of abuse against vulnerable students at a similar school. Moloney was sent to work at the seat of Catholic power at the Vatican in Rome.

McGrath returned to Christchurch in 1986 to start the Hebron Trust for at-risk kids in Christchurch, where he continued to abuse vulnerable children. This movement back and forth is called the “geographic cure,” a method for the Church to cover up abuse in one location by moving perpetrators elsewhere, where the offending inevitably continued.

Students at Marylands had also tried to escape and notify police separately. They were often picked up by police and returned to Marylands without being asked why they were trying to leave. Mr HZ, for instance, told the Commission that he had run to the police station and said that he was being abused; he was told he was lying, his complaint was ignored, and he was returned to the school.

Following allegations of abuse in 1992, McGrath was moved to a church “treatment facility” in the US. There is no evidence the institution investigated the claims fully. In 1993, after a police investigation, he was convicted of 10 offences and jailed for three years.

Clearwater says that “when MSSAT started working with survivors, many said that they’d tried to speak about it in the past and no-one had believed them.” Even as a survivor and advocate himself, he found it difficult to wrap his head around the scale of abuse. The disjointedness between the external perception of the brothers and the internal misery at Marylands made this more difficult. “The community described what a wonderful caring man McGrath was, and he was [actually] a nasty, sadistic man,” Clearwater says. “No-one would believe a six- or seven-year-old boy over a whole Catholic order.”

In 2002 and 2003 another investigation into abuse at Marylands was carried out, following a television documentary that led to survivors contacting the police. The police didn’t interview or seek out all victims. This led to McGrath being tried again in 2006 and Moloney in 2008.

Garchow, Marriott’s tormentor, was also up for trial, but the charges were deferred, as the elderly man was in poor health; he died in 2011. “I got told he had throat cancer,” Marriott says. In a cruel twist, Marriott was sick at the same time, with Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Nonetheless, he wanted to face the court, to speak directly to the man who had hurt him so profoundly, but he was denied the opportunity to do so.

During this period, then-leader of the St John of God Order, Peter Burke, met with multiple survivors along with Dr Michelle Mulvilhill, a former nun and psychiatrist. Some were offered ongoing pastoral care and given financial payouts. When criminal proceedings started, Burke put this on hold so as not to interfere with the process, saying it would restart after the trial. In 2007, Burke was replaced as leader, and the pastoral support did not continue.

“[Burke] genuinely wanted to help, but the rug was pulled from under him,” Clearwater says. “Many of the guys got angry at him for not keeping his promise.” Clearwater doesn’t think the church is sorry. “They’re just sorry they got caught.”

Wounds like this don’t heal

The Commission hearings about Marylands are over; their report into the school was published earlier this month. But Clearwater says the impact of what happened in this place, and the authorities that failed children repeatedly and at every level, will never be resolved. “It’s still happening, every day, in their heads. When that’s happened, you don’t know who to trust, and you’re constantly subject to the same system that put you there in the first place.” Many survivors have ended up in the care of the state one way or another, in the mental health system and in prisons, and the abuse at Marylands has made it much more difficult for survivors to trust institutions like the police, ACC, social workers and medical professionals.

“It’s blown all my trust with everyone,” Marriott says. “When it comes to government and people, the system has never been on my side, so why should I trust the system? They just shit on me.” He pauses and apologises for his use of bad language. “Even the Royal Commission – they were guiding us through the Commission, giving us nice food beforehand and stuff, and I kept saying no, I don’t want it. Whenever there’s something good, something bad happens.”

In Christchurch, Marylands has left a physical mark. There are the buildings in the Halswell location, still operating as a school, and there’s a street and a reserve named Marylands close to the original location in Middleton. “We need to get rid of this Marylands name,” Marriott says. “For a survivor it’s one of the worst things to hear and see.” The local board in the area has indicated that they will consider changing the name after the much-delayed delivery of the final report.

Survivors recognise how important it is to describe what happened to them: for solidarity with others who attended the school, and to raise wider awareness, including through the Commission process. It’s why Marriott is speaking to me. But after 30 years of various trials, criminal convictions, media reports and now the Commission, having to repeat the story can be difficult, too. This is a “double bind” for survivors, Clearwater says.

“Every time it gets brought up in the media, it sends me back,” Marriott says.

The fear and confusion of his experiences at Marylands have played into all of Marriott’s relationships since, and made it difficult for him to communicate. He spent many years drinking, just to get the confidence to talk to others, especially women. He has children, but struggled to talk to his wife, and they divorced.

Marriott and Clearwater both say it’s urgent for the Commission’s final report to consider how the abuse will be remembered. That final report, yet to be published, will address abuse throughout the country; for now, there is the Royal Commission’s report into Marylands, published at the start of August. Survivors, including Marriott, got to participate in the designing and naming of the document. But long, dense papers hidden as PDFs on government websites can’t bear the weight of the harm that has been done.

How will this dark part of our country’s history be remembered? Survivors are ageing, but atrocities of this scale require generational memory, a way to ensure the actions are never repeated. They agree that they want to see responses that are public. Marriott says that often coverage focuses on the clinical details: trials and convictions, police reports and numbers of staff that were involved. “It doesn’t take into account the survivors point of view, the feeling that, ‘I would never put my child in a situation like that,’ rather than the focus on the brothers.” He’d like to see a documentary solely focused on survivors, not the brothers: a way to acknowledge the grief, disappointment and trouble that sits beside him every day.

“There needs to be public memorials, named parks, a museum,” Clearwater says. “We need people to read these stories and see what happened to children in our country, to respond and say: what happened to you was wrong, it was evil, it should never have happened. As a society, we believe you.”

By Shanti Mathias

30/08/2023